by Jeremy LaCasse, Executive Director, gcLi, Assistant Head and Teacher of History, Taft School, Watertown, CT

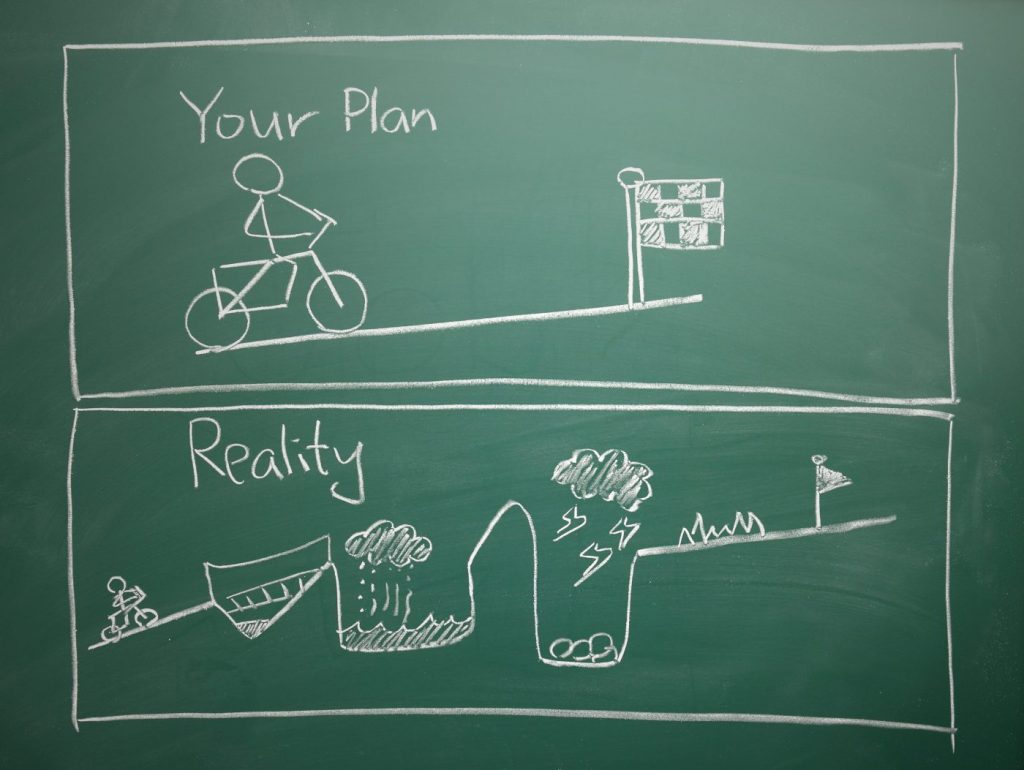

This moment has me thinking of three things. First, this moment requires an unrelenting commitment to be honest with ourselves and others about the reality of our circumstances. Those of us who are either eternal optimists or pessimists need to understand that this moment has both good and bad in it. Our glossing over or overly dwelling on the negative aspects of this moment can be hugely problematic as we work through these challenges. Jim Collins in his book Good to Great defined the “Stockdale Paradox,” a reference to a navy admiral who spent significant time as a prisoner of war during the Vietnam conflict. The paradox notes that a person must maintain unwavering faith that they will prevail, regardless of the challenges, and, simultaneously, “confront the brutal facts” of the situation. I would call this being optimistically realistic. This mindset allows a person to acknowledge and deal with the real and significant challenges faced while also finding the mental space to have hope in the future.

I have heard the term “toxic positivity,” which, in my way of thinking, is someone basically blind to reality, the counterbalance to simply being negatively toxic at all times. For those having to work with people so inclined, it’s easy to get frustrated about the person’s worldview and how limiting that worldview is in dealing with the reality of the situation. Jim Collins notes, “What separates people is not the presence or absence of difficulty, but how they deal with the inevitable difficulties of life.” Our willingness to deal with reality and to work to find ways through the challenges inherent in it are what will ultimately help us find our way through and on to the next set of difficulties. Remember, as a leader, you are looking to leave those who succeed you with a better class of problems than the ones you inherited from your predecessor.

A post to a teacher’s Instagram feed prompts my second thought. The post read, “Dear First Year Teacher, you’re not doing it wrong, it’s just really that hard. Signed, Been there, done that, made it through, and so will you” (@teacherexplore). Granted, I may be feeling a bit older than average as the other day I was granted, 16 years early, the senior discount at a local eatery. But, let’s focus on the key feelings in this note. Namely, our self-doubt and self-questioning as educators. We can forget that folks with more experience may also feel similarly when we are new to the gig (or even not-so-new). It’s essential to remind ourselves, perhaps more often than we do, that, while the work of educating children is truly challenging, our willingness to put forth our best effort, to call on resources and support, and to learn from each interaction increases our effectiveness. We will get through, together, and our students will continue to learn and grow, becoming the people they hope to be.

My third thought comes from Dr. Jennifer Bryan, who notes that we often confuse safety with comfort. The uncertainty of this moment is incredibly uncomfortable for so many of us. Some of this is born of legitimate safety concerns resulting from a global pandemic. Some of it is also of our own making, looking not at the brutal facts but at our discomfort as a gauge of how we should respond in this moment. Helping our communities tease apart safety from the discomfort is truly challenging work for a leader as the stakes are very high. A leader who does this well guides the entire community to become safer, functional, and trusting. A leader who misses the mark leaves individuals less trusting, more scared, and the community less functional and, as a result, less safe in the sense of being able to confront the real challenges faced by the community. Helping individuals navigate their individually devised discomfort is time-consuming and requires careful listening, thoughtful responses, and an openness to feedback.

Feedback, the only way to have an understanding of the impact of the moment and our behaviors on the group, is central to the leader’s ability to make informed choices that ultimately help the group to function well. A leader who solicits feedback increases the likelihood of confronting the “brutal facts,” helping others navigate this moment, and helping the group achieve a level of safety necessary to function.

Our work with our students has never been more important. The challenge and uncertainty of this moment requires that we do all we can to rise to this moment and work together to aid our students in navigating life. There is nothing easy about this moment, but I am certain that our students benefit from our best efforts. Franklin Roosevelt accurately defined moments like this in saying, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

I wish each of you the best of luck, acknowledge the value of the tremendous work you are doing, and offer whatever help and support I might provide. Be well and godspeed.

—

Jeremy LaCasse, Executive Director, gcLi, is also currently Assistant Head of School at the Taft School. LaCasse held the Shotwell Chair for Leadership and Character Development at Berkshire School. He also directed the Ritt Kellogg Mountain Program; served as Dean of the sixth and fourth forms; taught European history and Medieval history; and coached the ski and crew programs. Following his time at Berkshire, he served as the Dean of Students at Fountain Valley School of Colorado, and following FVS, he was the Head of senior school at Shady Side Academy in Pittsburgh, PA; the Head of Kents Hill School in Kents Hill, ME; and the Assistant Head of School at Cheshire Academy, in Cheshire, CT. He graduated with a B.A. in History from Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, and earned an M.A. in private school leadership from the Klingenstein Center, Teachers College at Columbia University.